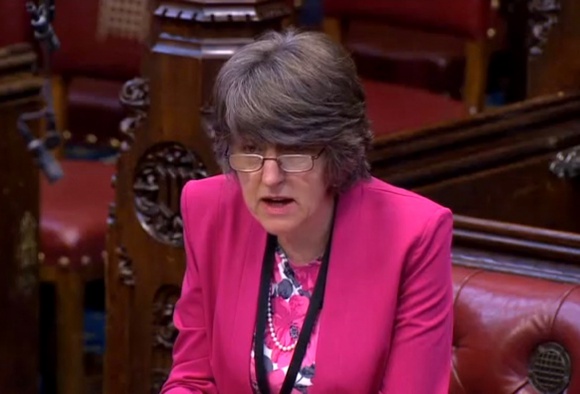

Days after the Commons threw out the Marris assisted suicide bill in September, 60 MPs signed an open letter calling for improved funding for palliative care, and with debate taking place in the House of Lords on Baroness Finlay's Access to Palliative Care Bill, news of further debate in the Commons was most welcome. Maria Caulfield (pictured) was one of a number of healthcare professionals who spoke out against assisted suicide on 11 September, and while adjournment debates do not feature a vote, it is increasingly clear that Parliamentarians take seriously their responsibility to give people with terminal and incurable illnesses and disabilities better support to live with dignity.

Miss Caulfield, a Conservative MP, said in her introduction:

... from my experience as a cancer nurse working in one of the best cancer units not only in the country but in Europe, I have seen at first hand the difference that good palliative care can make, not just to patients and their families at the time of death, but in the last few weeks and months, making patients' lives as fulfilling as possible.

She went on to discuss disparities in access to palliative care:

For me, palliative care is about support and services that help to achieve a good death and underpin the care in someone's final weeks and months of life. What happens now is that all too often the provision of palliative care is distributed on the basis not of need but of availability, and depends on the diagnosis, where the person is treated, and sometimes even their age, leading to a patchy and ineffective service... currently only 48% of people who have palliative care needs receive palliative care support. Of the 500,000 deaths that occur in this country every year, 82.5% are among the over-65s, yet fewer than 15% of that group have access to palliative care. That tells us that those who need it most often have the hardest job accessing it. For older people, death is often seen as inevitable and not something that palliative care should be helping with.

[...]

The London School of Economics says that 92,000 people a year miss out on palliative care help. At the moment, 88% of our palliative care provision goes to people with cancer. As a cancer nurse, I am certainly not saying that that needs to be reduced, but the majority of deaths are due to other diseases. Only 29% of people die of cancer, with 28% of deaths due to heart disease, 15% due to respiratory illnesses, 10% due to stroke, not to mention Alzheimer's disease, motor neurone disease and multiple sclerosis. Until we ensure that palliative care provision is mainstream, and not just for patients with cancer, the majority of people will be denied access to a good death.

Miss Caulfield also spoke to issues relating to accessing care around the clock, referencing her party's 'seven day NHS' plans but also touching on themes of reducing the burden on both patients and acute services by broadening access to dedicated palliative care:

The Bill fits very firmly into the Government's seven-days-a-week NHS in calling for the availability of seven-days-a-week palliative care services. As I know only too well, it is at 4.30 pm on a Friday that a patient will phone up in pain and say they cannot cope, when pharmacies are closed and it is possible to get a prescription but not a drug. Someone who is breathless and needs a chest drain often has to wait until the Monday morning, in the meantime being admitted to A&E or a medical assessment unit and then finding it very difficult to be discharged to go home. This is why we need a seven-days-a-week palliative care service.

The Bill calls for some really basic things that should exist now but do not, such as sufficient equipment for our community services. It is unbelievable that a ward nurse who wants to discharge someone with a morphine pump cannot do so because the pump belongs to the hospital. Unless the community has a spare pump, that patient will not go home. That is why only 30% of people are dying at home—they are stuck in hospital because communities do not have the necessary equipment to look after patients.

[...]

The Bill also highlights the fact that medication is not available at all times. I know only too well that if a patient's pain needs to be better controlled, they can get a prescription but they cannot get the drugs on a Saturday or Sunday or during the night. Once again, they are admitted to A&E for help in managing their pain. That is not acceptable.

She concluded:

The NHS is supposed to be there from cradle to grave, but this country is not getting death right. People are going abroad to commit suicide because they cannot face a natural death. We are doing something fundamentally wrong.

Responding on behalf of the Government, Health Minister Ben Gummer said:

I firmly believe that, unless the NHS understands that the basis of care is not the end point of healthcare but a good in and of itself, we will not build a satisfactory foundation for the medical care that we hope is the experience of the majority in the NHS. For people for whom the end point is not recovery, but good and decent care, we must ensure that such care is embedded in the foundations of the NHS. If we do not, we will not provide a suitable foundation for good care throughout the system. That is why I see palliative care not as something that is nice to have—an added extra or a bonus within the NHS—but as something that is crucial to the delivery of good care throughout the system, whether or not people are likely to survive at the end of their care in hospital, in the community or at home.

The theme of good palliative care not being 'an added extra' actually echoed Baroness Finlay's speech in the Lords, although Mr Gummer went on to outline why the Government was not supporting her bill. He brought up various existing examples of good practice from around the country, but was challenged by Labour MP Sarah Champion, who said:

The Minister is citing excellent examples, but does he agree with me—I think that this is the intention behind the debate—that we should not just have exceptional examples, but 24/7 care wherever people are and whatever their condition is?

The Government's view of Lady Finlay's bill aside, the Minister made clear that they accepted improvements must continue to be made:

There is much to do in some areas of the country. If I may use Bevan's words, it is about universalising the best. We know what the best looks like. We now need to ensure that we spread it across the rest of the country.

[...]

I hope that all parties can work together on this, calling on the experience of people from every part of the country—it was great to hear from the hon. Members for Torfaen (Nick Thomas-Symonds) and for Strangford (Jim Shannon), who shared their experience from other parts of the UK. If we can bring all this together, I think we can do something rather remarkable for people with no medical hope at the end of their life but to whom we should give the absolute guarantee that their care will be exceptional and will make what is never going to be a happy moment at least bearable and full of meaning for them, their families and their loved ones.

Read the debate in full.

(Image: Parliament TV screengrab - Open Parliament Licence)