This month, Twitter announced that some users would, as part of a trial, be able to send messages of 280, rather than 140, characters. To say that this of niche interest would probably still be to overstate the case, but CNK found that we too could suddenly go for longer than we thought. That thought led to another, very much more pertinent to our work.

Proponents for assisted suicide in the UK lionise the systems in place in the United States, notably the Oregon model, which allows lethal prescriptions to be made out to those assessed by two doctors as having less than six months to live. Here, Lord Falconer's 'commission' advised him to seek such a law for patients given a 12-month prognosis, but he followed Oregon and sought six. His bills in the House of Lords continually foundered, and his party colleague Rob Marris saw almost identical proposals rejected by 330-118 in September 2015.

Many have said that the requirement of a terminal prognosis stands simply to make proposals seem less extreme and more palatable than the much wider-ranging law people like the late Lord Joffe have said they would favour (a 'first step'). Campaigners like Baroness Campbell have said that such a law would be to set a door ajar - a door which would soon be opened wide enough for disabled people and others whose lives are considered of less value. She also said - as have many others - that such a line is arbitrary.

Why six months and not 12? Because it sounds easier to judge.

Physicians sitting in the House of Lords spoke authoritatively during consideration of the Falconer Bills about the limitations of predicting how long a terminally ill person will live. This is supported by academic research. In 2016 we learnt that:

'A review of more than 4,600 medical notes where doctors predicted survival showed a wide variation in errors, ranging from an underestimate of 86 days to an overestimate of 93 days.

'And it does not appear that more experienced or older doctors are any better at predicting when somebody will die than their younger counterparts.'

In 2017, a

'...study, conducted by researchers at the Marie Curie Palliative Care Research Department at UCL and published in BMC Medicine, looked at 26 previously published studies comprising 25,718 predictions made by clinicians using the "Surprise Question" over a ten-year period.'

'The "Surprise Question" was developed as a way to recognise those patients who might benefit from palliative care. It typically asks clinicians to consider the question: "Would you be surprised if this patient died within the next 12 months?"'

'The findings reveal that the accuracy of predictions varied considerably, with clinicians tending to over-predict the number of people whom they thought would die. Over half (54%) of those predicted to die within a specified time period, lived longer than expected.

'Clinicians made inaccurate predictions about one third of the patients who did die. Overall, they were incorrect in a quarter (25%) of cases.'

Doctors aren't very good at saying, really until the final days, when a patient will die. We know this, and we know they know this, because they are the ones who tell us this. Yet still, campaigners tell us a six month prognosis is a good way to define legislation on assisted suicide.

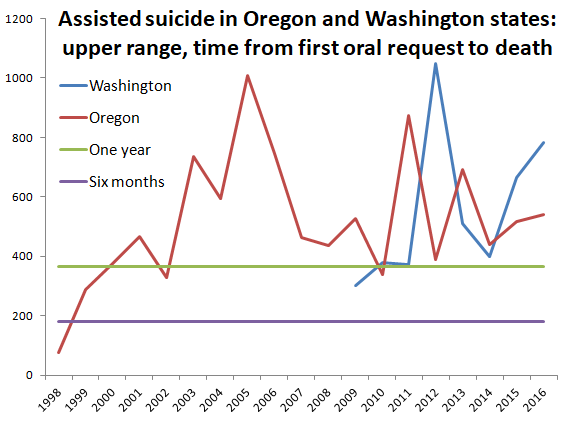

Between them, Oregon & Washington have 27 (documented) years' experience of assisted suicide (since 1998 and 2009 respectively). Only once - in the very first year of Oregon's experience - did no patients die outside the much-vaunted six months. In 22 of the 27 years, patients lived for more than a year after (successfully) requesting assisted suicide, and both states have seen patients live for almost three years. These are all patients assessed by two doctors who both agreed that they had less than six months to live.

We could say much about the many instances of doctors who have never met, much less treated, the patients before them before assessing their chances of survival. We could also say much about those doctors who statistically are clearing patients for death at a rate of one a fortnight (in 2016 alone, at least one Oregon physician wrote 25 prescriptions). We will however limit ourselves to observing the following: these figures, contained in annual reports, are the upper reaches of the first request to death 'range', and are accompanied by median figures. Advocates would say that the median figures are a truer guide, but that would be to miss the point.

Patients living six times longer than doctors told them they would when they agreed to enable their suicide is bad, because it reminds us that prognoses are a notoriously unreliable basis for a law on matters of life and death.

More significant, though, is this: how many patients who took lethal medication much sooner after receiving it might in fact have been destined to live much longer? How many patients - husbands and wives, parents and children, friends - were told they were closer to death than they were, that their will to die was understandable, and that not only would they not be talked down, but would actually be assisted? We cannot know.

A prognosis is a helpful way of informing the broad view, but it is simply absurd to say (a) that a life is worth less after a six month prognosis than before it, and that (b), the six month prognosis can even be relied upon. To turn again to Baroness Campbell:

It devalues lives, endangers vulnerable people - and cannot be considered to enhance proposed legislation.'The catch-all of six months sends the invidious message that once you are down, you are on your way out, that once death is on the agenda of life, it outweighs every other consideration. For any newly diagnosed individual, it allows the early seeds of fear and doubt to be sown...'

Each annual report includes data concerning 'Duration (days) between first request and death: Range.' The image above is based on the upper reaches of these ranges, listed below (with Washington's converted from weeks). The Washington report includes the deaths of all prescription recipients; Oregon only those who had ingested the drugs. The graph includes bars indicating the six-month (182 day) provision contained in the bill and, for further reference, a year (365) marker.

|

Oregon |

Year |

Washington |

|

75 |

1998 |

- |

|

289 |

1999 |

- |

|

377 |

2000 |

- |

|

466 |

2001 |

- |

|

329 |

2002 |

- |

|

737 |

2003 |

- |

|

593 |

2004 |

- |

|

1009 |

2005 |

- |

|

747 |

2006 |

- |

|

463 |

2007 |

- |

|

436 |

2008 |

- |

|

527 |

2009 |

301 |

|

338 |

2010 |

378 |

|

872 |

2011 |

371 |

|

388 |

2012 |

1050 |

|

692 |

2013 |

511 |

|

439 |

2014 |

399 |

|

517 |

2015 |

665 |

|

539 |

2016 |

784 |